It would involve the President promising to be a good boy and never to do it again except in the case of a real emergency…

What that would mean, based on what Utah Republican Mike Lee has put on paper, is the Senate wouldn’t block Trump’s declaration of a “national emergency to grab funding for his wall. But in exchange, the President would promise to sign a bill the Senate would then pass, making any future “emergencies” expire after 30 days without the express approval of Congress. Lee, along with a small group of other like-minded Senators, have been communicating with Vice-President Pence regularly to try to avoid the embarrassment of confronting Trump directly and publicly, while not shirking their duty to defend the Constitution. Tennessee Senator Lamar Alexander, who we talked about last week, is also part of that group. His idea has been for Trump to withdraw his national emergency declaration, and then let Congress help him find places he can draw money from to build the wall anyway without it.

But both those ideas might be at cross-purposes with Trump’s intentions: the President might want to follow through on his “National Emergency” for precisely the same reason some Republicans don’t want him to do it: it would weaken Congress’ ability to stand up to him in the future.

And that might make both plans being proposed by Republican Senators as unpalatable to the President as a medium-rare steak.

That’s also why we have some doubts about whether the President really cares if has to veto the resolution of disapproval. Even though the President’s declaration isn’t widely approved by the public, the stakes for Congress are much higher than they are for him. He’s already made his move.

There’s a third, even stranger plan: according to Politico, Republican Senator Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania is desperately trying to add language to the “resolution of disapproval” saying that the wall is great and should be built and there really is a crisis at the Southern border and Republicans voting against Trump are not disagreeing with that, just the way the President is going about getting the money. First of all, we don’t see why that matters. Secondly, the resolution of disapproval as passed by the House is short and sweet. That might be intentional in order to head of the kind of thing Toomey’s trying to do: making it likely Senate parliamentarians (they are experts on procedure who ultimately decide what is and isn’t kosher about a bill and the way it moves through the Senate) won’t allow the addition of a lot of flowery language.

As we showed you before, here’s that resolution, as it now exists, in its entirety:

So not much wiggle room there…

Trump keeps pushing back that he’s not attacking the Constitution, even though he clearly is. Since the Constitution clearly states Congress is in charge of raising and spending money, if Congress says he can’t have money for something, the President can’t just take it anyway. As we’ve said before, the President is like the CEO of a major public company: he’s responsible for implementing his vision, but does not typically own much of the company, and does not fund the company out of his own pocket. And while in some ways he’s more powerful day-to-day than the Board of Directors, if the board tells him he can’t do something, he can’t.

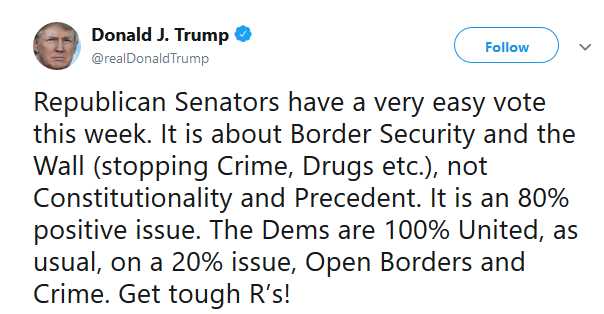

Trump either doesn’t, or won’t get that, Tweeting:

Although at the same time we really have no idea what the President’s talking about here. With “80% positive issue.” Huh?

No matter what, the Senate is going on vacation soon. So expect a vote on the “resolution of disapproval” that’s already passed in the House by tomorrow. (Believe us, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell would kill it if he could. But in this case, he can’t). Perhaps to nudge the President a little, McConnell’s been talking freely about passing legislation anyway to narrow the power of the President to declare national emergencies.

Quick Update To Our Story: Why The Fairness or Unfairness Of Manafort Sentence Isn’t All That Clear Cut

During the sentencing of Paul Manafort in as many weeks, Judge Amy Berman Jackson said a couple of things we think are worth noting.

First:

“There’s no question this defendant knew better, and he knew exactly what he was doing.”

Hardly the “otherwise blameless life” described by Judge T.S. Ellis during his sentencing last week in the first Manafort conviction. (See our original story below).

And:

“It’s not appropriate to say investigators haven’t found anything when you lied to the investigators.”

That was in reference to Manafort’s lawyers continually bringing up the “fact” that the government didn’t prove Manafort’s collusion with the Russian government. Judge Jackson called that contention a “non-sequitur”, since it had nothing to do with the charges against Manafort in this case, and therefore wasn’t a part of the trial. She did however acknowledge that Manafort and his lawyers might be intending those comments for a different audience. Making it known loud and clear while Manafort might’ve ratted on himself, but he didn’t rat on Trump.

In the end, Jackson sentenced Manafort Wednesday to 43-months for a second set of convictions. These involved a guilty plea on Manafort’s part, unlike his sentencing last week, which came after a jury finding him guilty. That new 3 1/2 year sentence, is also less than federal sentencing guidelines dictate. So now, in addition to the 4 year sentence he received last week, his prison time adds up to 7 1/2 years. Except the judge ruled some of it can be served concurrently, since he was found guilty for some of the same crimes in both cases. According to Politico, that’ll mean the longest he’ll be in prison is about 6 years from now, when all is said and done. Unless of course, Trump pardons him.

But that possibility just got a lot harder, because just as soon as Manafort’s sentencing concluded, the State of New York freshly indicted Manafort on 16 charges, including mortgage fraud, conspiracy, and falsifying records. While the President has the power to pardon anyone convicted of a federal crime, he doesn’t have the same power at the state level. Manafort’s lawyers are likely to argue he’s already been tried for the crimes he’s been accused of by New York, but its case may include allegedly fraudulent transactions that were not part of the federal charges.